Book Section: CHAPTER I — Omar Khayyam’s Annotated Persian Translation of Avicenna’s “Splendid Sermon” in Arabic on God’s Unity and Creation: The Manuscript with a New English Translation, Followed by Comparative Textual Analysis — by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi

$20.00

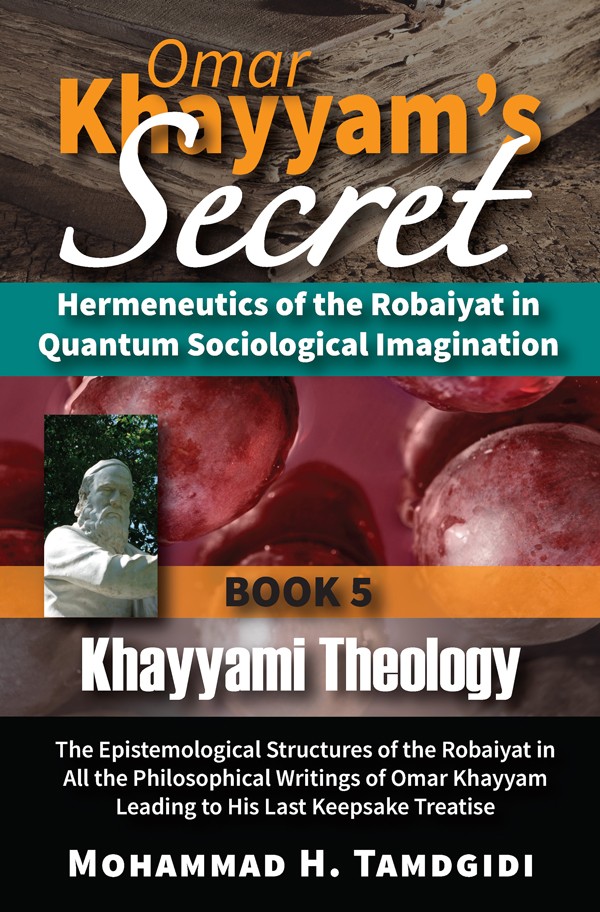

This essay titled “Omar Khayyam’s Annotated Persian Translation of Avicenna’s ‘Splendid Sermon’ in Arabic on God’s Unity and Creation: The Manuscript with a New English Translation, Followed by Comparative Textual Analysis” is the first chapter of the book Khayyami Theology: The Epistemological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Philosophical Writings of Omar Khayyam Leading to His Last Keepsake Treatise, which is the fifth volume of the twelve-book series Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination, authored by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi.

Description

Abstract

This essay titled “Omar Khayyam’s Annotated Persian Translation of Avicenna’s ‘Splendid Sermon’ in Arabic on God’s Unity and Creation: The Manuscript with a New English Translation, Followed by Comparative Textual Analysis” is the first chapter of the book Khayyami Theology: The Epistemological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Philosophical Writings of Omar Khayyam Leading to His Last Keepsake Treatise, which is the fifth volume of the twelve-book series Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination, authored by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi.

In the year 472 LH (AD 1079-1080), Omar Khayyam was invited in Isfahan by some who he referred at the time as “brothers” to translate into Persian a sermon originally written and delivered in Arabic by Avicenna (or Ibn Sina). In this chapter, Tamdgidi offers the original text in Persian, and his new English translation of it, before analyzing Khayyam’s interpretive and annotated translation of Avicenna parallel to the latter’s original text in Arabic.

The findings of this chapter can be summarized as follows.

While Khayyam faithfully translates Avicenna’s “Splendid Sermon,” he does so interpretively, offering his own views and preferred ways of stating the same. Khayyam demonstrates his independent-mindedness in translating Avicenna, in most part trying to offer his own views by way of amplifying Avicenna’s in subtle ways that are different from how they are expressed in the original sermon.

Khayyam is clearly and repeatedly, and in different ways, introducing the notion of succession order, in particular in terms of the notion of everything coming from and concluding in God, a notion not readily expressed as such in Avicenna’s original, though in substance Khayyam finds Avicenna’s views resonating with his own. The particular formulation of descending and ascending journeys may be Khayyam’s, which may explain why in “Resalat fi al-Kown wa al-Taklif” (“Treatise on the Created World and Worship Duty”), as we will study in the next chapter of this book, he alludes to that notion as a joint effort, rather than one of being merely Avicenna’s that he simply follows. The fact that Khayyam introduces the idea separately into his translation of Avicenna may be expressive of his own contribution to Avicenna’s worldview. For reasons that may have to do with the audience for whom and the socio-political conditions in which he was offering his translation, Khayyam uses subtle rhetorical devices when introducing God’s power in favor of the values of justice and self-determination.

Tamdgidi does not find anything in this translation effort by Khayyam that indicates a fundamental difference between his final worldview expressed in his last treatise on the universals of existence written about a decade and a half later. Perhaps this translation effort may be regarded as one of the occasions that allowed Khayyam to formulate his own views more carefully, a final expressions of which would find its way into his last treatise.

In particular, the notion that humankind becomes human when it awakens to its position in the succession order, a view stated in his last treatise more explicitly, is subtly present in Khayyam’s translation of Avicenna. The notion that humankind is somehow automatically “the purpose of creation”—short of the conscious and intentional effort needed on its own for self-purification—is problematized here differently, as part of the discussion of the unattributability of a purpose to God, since ultimately, it is humankind’s own efforts that will determine whether or not it would ascend nearer to God spiritually.

While Khayyam’s interpretive/annotated translation is of an ontological nature, one can discern also important epistemological patterns in the way Khayyam goes about describing the nature of reality, be it Avicenna, the nature of the universe, or even God. Khayyam seems to be highly aware of the fact that one cannot readily take oneself out of the object one is trying to describe. So, in offering his names for God, in interpreting Avicenna’s notion of God’s purpose, in describing what makes (or not) humankind special, in repeatedly introducing the notion of “everything comes from and returns to God” (when it is not expressed in the text he is translating), Khayyam is not only describing but also shaping that which he is reporting. He is not just saying what Avicenna said, but he is also shaping how he can be (in his view) better understood. This subtle pattern in Khayyam’s approach to his subject arises from his conceptualist epistemological approach to understanding reality.

By distinguishing substances which do not necessarily accept contradictions (angels, celestial bodies) and substances that do (such as humankind), Khayyam in effect says that beings (such as human) do not have to live in contradiction (since they are substance, and necessary creations of God), and if they do accept them, it is because of their own efforts, or lack thereof. This means, if substances are aligned with God’s emanations, they don’t have to be divided and conflictual.

Avicenna’s sermon and Khayyam’s translation of it significantly discuss the problem of unity and multiplicity. This may be another occasion where we find Khayyam reflecting on Avicenna on the subject of “the one and the many”—a topic on which Khayyam was contemplating, having Avicenna’s book al-Shafa in hand, on his last day.

By way of Avicenna’s text and his translation of it affirmingly, Khayyam once again demonstrates a view in which spiritual development and purification depend on becoming detached from material interests. Matter is regarded as a hindrance in this scheme.

The notion that one can go about describing anything (be it Avicenna, or God) as if there is an “objective” reality out there without the intervention of the life and views of those who do the describing, seems to be problematized in Khayyam’s scientific practice. So, even when he is translating Avicenna, per invitation of his “brothers,” to tell them what he said in his sermon, Khayyam is consciously, yet subtly, using the occasion to shape the educational event in ways that imply he himself is an active agent in shaping the reality he is describing.

Khayyam’s contribution is not just ontological, that is, about the nature of God, about the nature of the existence, about the nature of universe, and so on. The contribution is also at the same time epistemological. Khayyam’s conceptualist approach allows him to demonstrate that the reality God has created is a malleable, flexible, itself creative, medium, which cannot be simplistically dualized into the object and a subject. The subject, for him, is a part of the object. Humankind does not become human unless it becomes conscious of its place in the succession order. The active intellection, one that goes all the way back to the first active intellect, is also present in him or her and defining what humankind can, and is supposed to, be. So, Khayyam demonstrates the same by actively translating Avicenna in such a way that renders him also as a co-author of Avicenna’s sermon.

There is a seemingly minor omission or silence in Khayyam’s translation of Avicenna’s last concluding clause that we will have to return to when studying Khayyam’s other treatises in this book. It has to do with the direct reference Avicenna makes to praying and fasting and forms of worship, which are generally alluded to, but not specifically, in Khayyam’s interpretive translation. Instead of elaborating on this topic here, we will try to return to it in the following and later chapters of this volume. We also should keep in mind, and this is hermeneutically important, that there was no explicit discussion of an after-worldly heaven or hell in Avicenna’s sermon, nor in Khayyam’s interpretive and annotated translation of him.

Recommended Citation

Tamdgidi, Mohammad H. 2022. “CHAPTER I — Omar Khayyam’s Annotated Persian Translation of Avicenna’s “Splendid Sermon” in Arabic on God’s Unity and Creation: The Manuscript with a New English Translation, Followed by Comparative Textual Analysis.” Pp. 17-84 in Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination: Book 5: Khayyami Theology: The Epistemological Structures of the Robaiyat in All the Philosophical Writings of Omar Khayyam Leading to His Last Keepsake Treatise. (Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge: Vol. XVIII, 2022. Tayyebeh Series in East-West Research and Translation.) Belmont, MA: Okcir Press.

Where to Purchase Complete Book: The various editions of the volume of which this Book Section is a part can be ordered from the Okcir Store and all major online bookstores worldwide (such as Amazon, Barnes&Noble, Google Play, and others).

Read the Above Publication Online

To read the above publication online, you need to be logged in as an OKCIR Library member with a valid access. In that case just click on the large PDF icon below to access the publication. Make sure you refresh your browser page after logging in.