Khayyam’s Robaiyat are the millennial rebirth songs of his poems’ hidden Simorgh, served in his tented tavern as 1000 sips of his bittersweet Wine of happiness.

GREATER BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, UNITED STATES, October 29, 2024 — Sociologist Mohammad H. Tamdgidi, Ph.D., research director at OKCIR (Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research), released in October 2024 Books 8-11 of his “Omar Khayyam’s Secret” Series dedicated to presenting his complete collection of the Robaiyat including the original Persian quatrains as well as his new English verse translations of them.

To read this press release post in Persian (نشرنامه فارسى) please click here. To read the original press release, click here.

The 12-book series titled “Omar Khayyam’s Secret: Hermeneutics of the Robaiyat in Quantum Sociological Imagination” is being published in celebration of Khayyam’s true birth date (AD 1021) millennium and in commemoration of the ninth centennial of the true date (AD 1123) of his passing as a 102-year centenarian, whose discovery was reported and reconfirmed in Books 2 and 3 of the series.

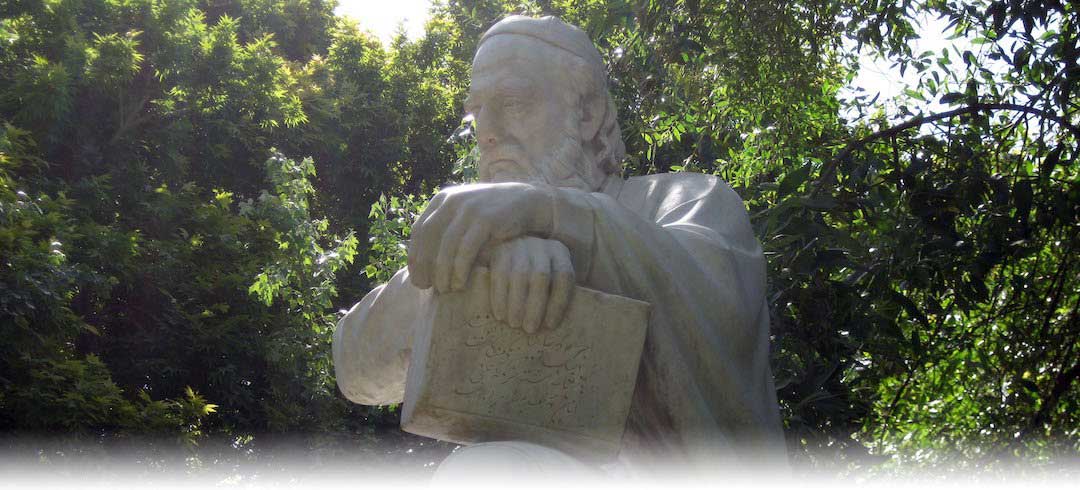

In the series, Tamdgidi has been sharing since 2021 the results of his long-standing research on Omar Khayyam, the enigmatic 11th/12th centuries Persian Muslim sage, philosopher, astronomer, mathematician, physician, writer, and poet from Neyshabour, Iran, whose life and works have remained behind a veil of deep mystery. The purpose of his research has been to find definitive answers to the many puzzles still surrounding Khayyam, especially regarding the existence, nature, and purpose of the Robaiyat in his life and works. To explore the questions posed in the series, Tamdgidi has applied a new hermeneutic method of textual analysis, informed by what he calls the quantum sociological imagination, to gather and study all the attributed philosophical, religious, scientific, and literary writings of Khayyam.

Book 8 is subtitled “Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 1 of 3: Quatrains 1-338: Songs of Doubt Addressing the Question ‘Does Happiness Exist?’” Book 9 is subtitled “Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 2 of 3: Quatrains 339-685: Songs of Hope Addressing the Question ‘What Is Happiness?’” Book 10 is subtitled Khayyami Robaiyat: Part 3 of 3: Quatrains 686-1000: Songs of Joy Addressing the Question ‘Why Can Happiness Exist?’” The three are explained with new English verse translations and organized logically following Omar Khayyam’s own three-phased method of inquiry. Each quatrain is indexed according to the frequency of its inclusion in manuscripts, the earliest known date of its appearance in them, the extent to which it has “wandered” into other poets’ works, and its rhyming scheme. Brief comments about the meaning of each quatrain in relation to other quatrains and works attributed to Khayyam are then offered along with any notes regarding its new translation as shared. Book 11, subtitled “Khayyami Robaiyat: Re-Sewing the Tentmaker’s Tent: 1000 Bittersweet Wine Sips from Omar Khayyam’s Tavern of Happiness,” sews Books 8-10 together.

In Book 8, Tamdgidi offers the first of the three-part set of 1000 quatrains he has chosen to include in this series from a wider set that have been over the centuries attributed to Khayyam.

He shows that the quatrains 1-338, in the beginning 30 of which Khayyam offers an opening to his book of poetry as a secretive work of art, address the question “Does Happiness Exist?” The latter question is the first of a set of three methodically phased questions Khayyam has identified in his philosophical works as being required for investigating any subject. The order in which the quatrains are presented shows that the quatrains included in Part 1 follow a logically inductive reasoning process through which Khayyam delves from the surface portraits of unhappiness to their deeper chain of causes to answer his question. The thematic topics of the quatrains of Part 1 as shared in Book 8 are: I. Secret Book of Life; II. Alas!; III-Times; IV-Spheres; V. Chance and Fate; VI. Puzzle; VII. O God!; VIII. Tavern Voice; and IX. O Wine-Tender!

After the opening quatrains where Khayyam explains why he was composing a secretive book of poetry and what it aims to do, his inquiry starts with doubtful existential self-reflections on his life, leading him to first blame his times, then the spheres, then matters of chance and fate, soon realizing that he really does not have an explanation for the enigmas of existence, concluding that the answer only lies with God. So, he appeals to God directly for an answer. It is then that he hears the voice of the Saqi or Wine-Tender from his inner “tavern,” to whom he replies in a series of quatrains closing Part 1.

It is in the course of the inquiry in Part 1 that the idea of using Wine as a poetic trope is discovered by him, a matter that is separate from his interest in drinking wine, which he never denies but is secondary to the spiritual Wine discovered and advanced in his book of poetry that in fact represents his poetry, the Robaiyat, itself and its promise in answering his questions.

The logical order of Khayyam’s inquiry shows how seemingly contradictory views that have been attributed to him can in fact be explained as logical moments in the successively deeper inquiries he makes inductively when addressing the question whether happiness exists in the created world. His inquiry is at once personal and world-historical, as two sides of expression of the human search for an answer.

In Book 9, Tamdgidi offers the second of a three-part set of 1000 quatrains he has chosen to include in this series.

He shows that the quatrains 339-685 address the question “What Is Happiness?” The latter is the second of a set of three methodically phased questions Khayyam has identified in his philosophical works as being required for investigating any subject. The order in which the quatrains are presented shows that the quatrains included in Part 2 follow a logically deductive reasoning process through which Khayyam advances in the causal chain of moving from methodological to explanatory and practical quatrains, by way of addressing the question noted above. The thematic topics of the quatrains of Part 2 as shared in Book 9 are: X. The Drunken Way; XI. Willfulness; XII. Foes and Friends; XIII. Wealth; XIV. Today; XV. Pottery; XVI. Cemetery; and XVII. Paradise and Hell.

Khayyam begins with reflections on God’s created world, suggesting that its unitary existence cannot be understood using either/or dualistic lenses where the ways of knowing by the head, the heart, and senses are pursued separately. Instead, he advocates, building on the idea of the Wine trope discovered in Part 1, a “Drunken way” by which he means a unitary way of knowing symbolized by the spiritual indivisibility of Wine in contrast to the fragmentations of the grapes. He then embarks on a deductive method of emphasizing human willfulness, also created by God, offering humankind a chance for playing a creative role in shaping its own world. Khayyam then continues to apply such an explanatory model in dealing with social matters having to do with foes, friends, and wealth, leading him to advocate for the practical significance of “stealing” the chances offered in the here-and-now of today to transform self and society in favor of happier and more just outcomes.

Using the tropes of visiting the jug-maker’s shop and the cemetery, he then emphasizes the need to maintain a wakeful awareness of the inevitability of one’s physical death to use the opportunity of life to cultivate universal self-awareness before it is too late, that paradise and hell and judgment days are not otherworldly, but realities of our here and now living. He thus transcends the sentiment of a promised future hope by advising us to create a happy life in the cash of the here-and-now, his own poetry itself being a means toward that end.

In Book 10, Tamdgidi offers the third of a three-part set of 1000 quatrains he has chosen to include in this series.

He shows that the quatrains 686-1000 address the question “Why Does (or Can) Happiness Exist?” The question is the third of a set of three methodically phased questions Khayyam has identified in his philosophical works as being required for investigating any subject. The order in which the quatrains are presented shows that the quatrains included in Part 3 continue the logically deductive reasoning process started in Part 2, but serve as practical examples of how humankind can turn the activity of poetry writing itself as a source of joy in life when confronting the topics of death, survival, and spiritual fulfillment. The thematic topics of the quatrains of Part 3 as shared in Book 10 are: XVIII. Garden; XIX. Wine; XX. Love; XXI. Night; XXII. Death and Survival; XXIII. Liberation; and XXIV. Return.

Khayyam’s overall sentiment in pursuing the inquiry in the third part of his book of poetry is expressive of joy. He begins by showing, using the example of his own poetry, how strolling in a garden offers opportunities to enjoy it even when writing about the transient nature of the roses and greens. He then offers in the longest section of his book a set of quatrains in praise of Wine, disguising therein a praise of the joy of writing his own poetry, Wine’s metaphorical double-meanings offering chances in the here-and-now of stealing joyfulness even when mistreated by his foes and amid feelings of helplessness in confronting physical death. He then turns to the topic of spiritual Love, signifying the role the sentiment of Love in search of the Source of creation plays in the evolutionary process of the succession order of the created existence as discussed in his philosophical and theological writings.

Khayyam continues to the topic of death and the possibility of lasting spiritual survival and existence by practically encouraging the Drinkers of the Wine of his poetry itself to help bring about that end. He ends the Wine of his poetry by expressing how it has helped free himself from the prior (in Part 1) doubtfully expressed inevitability of physical death in favor of not just hopefulness (in Part 2) but the certainty of having initiated a lasting spiritual existence by way of the bittersweet Wine of his poetry itself, celebrating a return to the spiritual Source of all existence as woven into the 1000-threaded wick of the candle of his Love for God.

In Book 11, having shared the three parts of the Robaiyat attributed to Khayyam in the Books 8, 9, and 10 of the series, Tamdgidi offers the entire set of the 1000 quatrains, including the Persian originals and his new English verse translations for each. The poems, comprising Khayyam’s songs of doubt, hope, and joy, are organized according to the three-phased method of inquiry he introduced in his philosophical writings, respectively addressing the questions: “Does Happiness Exist?”; “What Is Happiness?”; and “Why Does (or Can) Happiness Exist?”

When Khayyam discussed the three-phased method of inquiry in his treatise “Resalat fi al-Kown wa al-Taklif” (“Treatise on the Created World and Worship Duty”), he noted an exception to the rule of asking, when studying any subject, whether it exists, what it is, and, why it exists (or can exist). He distinguished between things objectively existing independent of the human mind, and those created by the human mind. The normal procedure applies to the former, but for products of the human mind, he advised, the procedure must be modified to asking first what something is, then, whether it exists, and then, why it exists or can exist. This is because, for products of the human mind, such as created works of art, we would not know whether something exists and why it exists unless we first know what it is. To illustrate his point, he used the example of the mythical bird Anqa (Simorgh in Persian or the Phoenix in English). He argued that only when we know what the metaphor stands for would we be able to say whether it exists (say, in a work of art, or even as a person represented by it), and why it exists or can exist.

Khayyam’s elaboration implies that one must make a distinction between objective and human objectified realities, which implies that for some objects, such as happiness, we in fact confront a hybrid reality where aspects of it may be externally conditioned, but other aspects being dependent on the human will. Once we realize the significance of Khayyam’s point, then, we appreciate that his Robaiyat can also be regarded as a way of poetically portraying and advancing human happiness, its poetic Wine being not just reflective but also generative of the happiness portrayed. By way of his poetry, therefore, Khayyam has offered a severe critique of the then prevalent fatalistic astrological worldviews blaming human plight on objective conditions, in favor of a conceptualist view of reality in which happiness can be achieved despite the odds, depending on the creative human agency, itself being an objective force.

Tamdgidi further shows that the triangular geometry of the logic governing Khayyam’s Robaiyat—the numerical values of whose three sides are proportional to the dazzling Triplicity or Grand Tent (in Persian “khargāh”) governing Khayyam’s birth chart—further supports the view (expressed in Khayyam’s own quatrains) that for him his Robaiyat poetically represented the tent of which he regarded himself to be a tentmaker, revealing another key explanation for his pen name. The geometric structure of a tent proportional to the Grand Tent of Khayyam’s chart, as well as the metaphor of the Robaiyat as Simorgh songs, are hidden in the deeper structure of Khayyam’s 1000-piece solved puzzle, the same way he embedded his own triangular golden rule in the design of the North Dome of Isfahan. Khayyam’s Robaiyat are his Simorgh’s millennial rebirth songs served in his tented tavern as 1000 sips of his bittersweet Wine of happiness.

Breaking a wine cup whose parts are so intertwined

Would not be condoned by drunkards or so inclined.

Who joined in love, then, and who broke so hatefully,

The dear heads and feet of many a humankind?

The good and the bad that are found in humankind,

Or the joys and sorrows that are chanced or destined,

Don’t blame on the wheel since, as far as wisdom goes,

The wheel has a thousand times less choice than your mind.

From the beginning, I searched by way of the sky

To find where the tablet, pen, heaven, or hell lie.

Then the teacher told me, “From the right point of view,

The pen of fate, paradise, or hell, is your ‘I.’”

“Khayyam! Even though your Grand Tent of the blue wheel

Was fastened but its door to talk remained in seal,

Like the Wine’s froth in being’s Cup, the Wine-Tender

Will eternally a thousand Khayyams congeal.”

— Omar Khayyam (Tamdgidi translation)

Books 8-11 have just been released and are now available at OKCIR and Google Play (PDF and Epub formats) for digital purchase or OKCIR Library online reading. Further digital (Epub format) and print editions will soon be available at major online bookstores worldwide and via OKCIR.

About the Author:

Mohammad H. Tamdgidi is the founding director of OKCIR: Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research in Utopia, Mysticism, and Science (Utopystics) (www.okcir.com) which has served since 2002 to frame his independent research, teaching, and publishing. He is a former associate professor of sociology specializing in social theory at UMass Boston.

Mohammad H. Tamdgidi

OKCIR: Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research

[email protected]

PREVIEW

PREVIEWNOCOVERofKHB-8-9-10-11-E